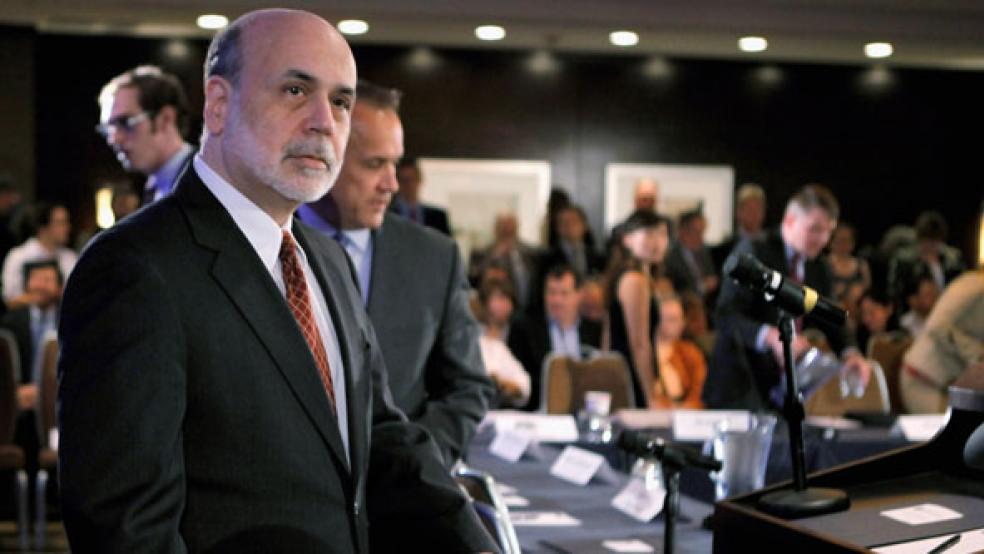

Federal Reserve Board chairman Ben Bernanke on Tuesday threw his considerable political weight behind a proposal for capping the still-rising national debt as a share of the economy and establishing policies that ensures it declines over the coming decades.

In a keynote address to the annual meeting of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, the nation’s top monetary official called for setting “clear metrics” to bring down the deficit, which is estimated to reach $1.4 trillion this fiscal year. The long-term goal, he said, should be linked to a budget enforcement trigger mechanism that will give the plan credibility.

At the same time, he reiterated his warning that the debt ceiling “is the wrong tool” for negotiating major spending cuts and that any deficit-reduction plan should avoid large budget cuts in the short run, since that could short-circuit the fragile economic recovery.

“Policymakers could commit to enacting in the near term a clear and specific plan for stabilizing the ratio of debt to GDP [gross domestic product] within the next few years and then subsequently setting that ratio on a downward path,” he said. “To make the framework more explicit, the President and congressional leadership could agree on a definite timetable for reaching decisions about both shorter-term budget adjustments and longer-term changes.”

Bernanke didn’t offer a specific goal for reducing the total national debt as a percentage of the economy. The current national debt of $14.3 trillion is approximately 90 percent of GDP. The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, for instance, promotes lowering the debt-to-GDP ratio to 60 percent by 2018 on its website.

The National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform also proposed reducing the debt to 60 percent of GDP, but by 2023, and to 40 percent of GDP by 2035.

Budget enforcement measures such as the Graham-Rudman Balanced Budget Act of 1986 and the Budget Enforcement Act of 1990 have been tried before with varying degrees of success. But they may be key to reaching an accord to raising the debt ceiling, which administration officials say must be done before August 2. Congressional Republicans are demanding deep spending cuts over the coming decade in return for their support for raising the debt ceiling. But they are also seeking guarantees that the budget agreement is enforced – possibly with mandatory spending caps and automatic cuts that would be triggered if Congress fails to stick with the agreement.

Talks led by Vice President Joe Biden aimed at reaching an accord continued Tuesday. The president’s top economic aide, Gene Sperling, arrived late at the conference after attending the latest session, saying that “progress continues to be made.”

House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan, R-Wis., , speaking during a roundtable discussion after Bernanke’s speech, opened the door to possible compromise on the core Republican position of allowing no new taxes in a deficit-reduction plan. Asked directly by Sen. Robert Bennet, D-Colo., whether he would consider a proposal that included one dollar in new revenue for every three dollars in budget cuts – the formula outlined by the president’s Bowles-Simpson deficit commission last December – Ryan replied, “Let’s see the path.”

After Ryan’s departure, Sperling arrived and was told by moderator Steve Liesman of CNBC that the Republican chairman of the House Budget Committee had endorsed the expiration of the Bush tax cuts (which he did not). Sperling replied, “I have not gotten that email yet. I have not gotten that Twitter. I have not gotten that phone call.”

Whether Ryan’s limited opening leads to more substantive progress in the debt ceiling talks in the days ahead will depend on both Republicans and Democrats compromising on core issues. Ryan reiterated his support for reining in Medicare spending by providing future seniors with limited financial support for purchasing individual insurance plans, which Democrats have turned into a major campaign issue in next year’s election.

For his part, Sperling said that any serious budget negotiations had to include revenue increases. “It’s impossible for the numbers to work without new revenues,” he said, and vowed that Democrats would never agree to any plan that included the draconian cuts to Medicaid included in the Republican budget that passed the House last March. “However we work this out, we should not default to asking those with the least political power to make the overwhelming bulk of the economic sacrifice,” he said.

Meanwhile, the latest prognostications from the nation’s banking community provided little solace for those hoping a surge in economic growth would help the nation rapidly grow its way out of its deficit woes. The American Bankers Association’s economic advisory committee, after a two-day meeting with top Fed officials, released an annual forecast that showed economic growth at only 3 percent for the next year, which they projected would add about 200,000 jobs a month.

The group said there is now just a 15 percent chance of a double-dip recession, although the outcome of the debt ceiling talks could reduce their projections for economic growth by as much as half a percentage point. “My expectation is that the cuts will be phased in over time,” said Peter Cooper, chairman of the committee and the chief economist at Deutsche Bank.

Related Links:

Fed Chairman Rules Out Higher Interest Rates for Now (The Fiscal Times)

Medicare, Medicaid Get Squeezed in Ryan Plan (The Fiscal Times)

The Economy: Lower Growth, Higher Unemployment (The Fiscal Times)