Trouble for Tesla: Why Consumer Reports Says Its Model S Was ‘Undriveable’

Consumer Reports in 2013 gave the Telsa Model S the highest rating of any vehicle in its history. This year’s review did not go as well for Elon Musk’s company.

The venerable magazine had to delay testing of the company’s newest model because its drivers couldn’t open the doors on the $127,000 sedan, temporarily making the car “undriveable.”

The door handles on the Model S P85 retract automatically and lay flush against the vehicle when they are not in use. Once the vehicle receives a signal from the key fob, the handles move to allow people to grip them. Unfortunately, the door handles stopped working after Consumer Reports testers had the vehicle for 27 days and had driven just over 2,300 miles.

That malfunction caused other problems, the magazine says: “[S]ignificantly, the car wouldn't stay in Drive, perhaps misinterpreting that the door was open due to the issue with the door handle.”

Consumer Reports’ troubles aren’t unique. The non-profit’s car reliability survey found that the Model S has had a far higher than average number of problems with doors, locks and latches, according to the organization’s website.

The testing experience wasn’t all bad, though, because the automaker’s customer service is top notch. A technician was sent to the Consumer Reports Auto Test Center the morning after the problem was reported and quickly diagnosed the problem.

“Our car needed a new door-handle control module — the part inside the door itself that includes the electronic sensors and motors to operate the door handle and open the door,” Consumer Reports says. “The whole repair took about two hours and was covered under the warranty.”

Eric Lyman, vice president of industry insights at TrueCar, told The Fiscal Times that the speed in which Tesla addressed that issue will earn it more kudos from customers who have seen carmakers drag their feet in making needed repairs. The door handle issue isn’t a big deal, he said.

“Telsa is still a relatively new automaker,” he said. “The reality is that we see this kind of thing happen all of the time. This is pretty normal in the course of business in the auto industry.”

The timing of the mishap comes as Telsa is struggling to repair its credibility with Wall Street after the electric vehicle maker’s disappointing earnings performance. Bloomberg News reported last week that the Palo Alto, Calif.-based company might have to raise money because of what one analyst described as its “eye watering” cash burn rate, or else it might run out of money in the next three quarters.

The electric vehicle maker also is facing increased competition from more established rivals. General Motors (GM), for instance, recently unveiled a Chevrolet Bolt concept car that is set to hit the market in 2017 with a projected price of about $30,000 and a battery range of 200 miles. The next generation Nissan Leaf, another electric vehicle, will hit the market at about the same time.

For now, Tesla’s biggest challenge may in convincing consumers to buy electric vehicles while oil remains cheap.

The High Cost of Child Poverty

Childhood poverty cost $1.03 trillion in 2015, including the loss of economic productivity, increased spending on health care and increased crime rates, according to a recent study in the journal Social Work Research. That annual cost represents about 5.4 percent of U.S. GDP. “It is estimated that for every dollar spent on reducing childhood poverty, the country would save at least $7 with respect to the economic costs of poverty,” says Mark R. Rank, a co-author of the study and professor of social welfare at Washington University in St. Louis. (Futurity)

Do You Know What Your Tax Rate Is?

Complaining about taxes is a favorite American pastime, and the grumbling might reach its annual peak right about now, as tax day approaches. But new research from Michigan State University highlighted by the Money magazine website finds that Americans — or at least Michiganders — dramatically overstate their average tax rate.

In a survey of 978 adults in the Wolverine State, almost 220 people said they didn’t know what percentage of their income went to federal taxes. Of the people who did provide an answer, almost 85 percent overstated their actual rate, sometimes by a large margin. On average, those taxpayers said they pay 25.5 percent of their income in federal taxes. But the study’s authors estimated that their actual average tax rate was just under 14 percent.

The large number of people who didn’t want to venture a guess as to their tax rate and the even larger number who were wildly off both suggest to the researchers “that a very substantial portion of the population is uninformed or misinformed about average federal income-tax rates.”

Why don’t we know what we’re paying?

Part of the answer may be that our tax system is complicated and many of us rely on professionals or specialized software to prepare our filings. Money’s Ian Salisbury notes that taxpayers in the survey who relied on that kind of help tended to be further off in their estimates, after controlling for other factors.

Also, many people likely don’t understand the different types of taxes they pay. While the survey asked specifically about federal taxes, the tax rates people provided more closely matched their total tax rate, including federal, state, local and payroll taxes.

But our politics likely play a role here as well. People who believe that taxes on households like theirs should be lower and those who believe tax dollars are spent ineffectively tended to overstate their tax rates more.

“Since the time of Ronald Reagan, American[s] have been inundated with messages about how high taxes are,” one of the study’s authors told Salisbury. “The notion they are too high has become deeply ingrained.”

Wealthy Investors Are Worried About Washington, and the Debt

A new survey by the Spectrem Group, a market research firm, finds that almost 80 percent of investors with net worth between $100,000 and $25 million (not including their home) say that the U.S. political environment is their biggest concern, followed by government gridlock (76 percent) and the national debt (75 percent).

Trump’s Push to Reverse Parts of $1.3 Trillion Spending Bill May Be DOA

At least two key Republican senators are unlikely to support an effort to roll back parts of the $1.3. trillion spending bill passed by Congress last month, The Washington Post’s Mike DeBonis reported Monday evening. While aides to President Trump are working with House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) on a package of spending cuts, Sens. Susan Collins (R-ME) and Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) expressed opposition to the idea, meaning a rescission bill might not be able to get a simple majority vote in the Senate. And Roll Call reports that other Republican senators have expressed significant skepticism, too. “It’s going nowhere,” Sen. Lindsey Graham said.

Goldman Sees Profit in the Tax Cuts

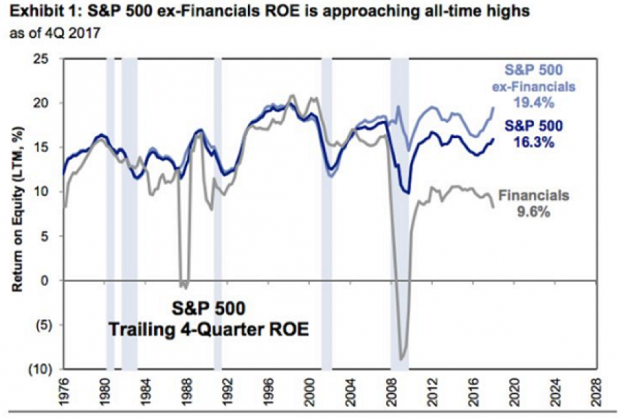

David Kostin, chief U.S. equity strategist at Goldman Sachs, said in a note to clients Friday cited by CNBC that companies in the S&P 500 can expect to see a boost in return on equity (ROE) thanks to the tax cuts. Return on equity should hit the highest level since 2007, Kostin said, providing a strong tailwind for stock prices even as uncertainty grows about possible conflicts over trade.

Return on equity, defined as the amount of net income returned as a percentage of shareholders’ equity, rose to 16.3 percent in 2016, and Kostin is forecasting an increase to 17.6 percent in 2018. "The reduction in the corporate tax rate alone will boost ROE by roughly 70 [basis points], outweighing margin pressures from rising labor, commodity, and borrow costs," Kostin wrote.