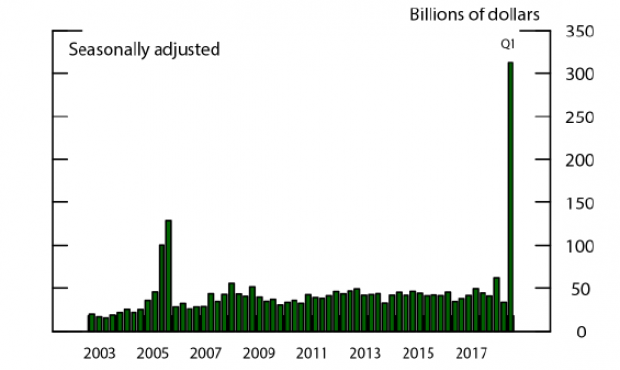

There was a huge spike in the return of foreign profits to the U.S. during the first quarter of 2018, according to an analysis from the Federal Reserve released Tuesday.

The tax legislation that went into effect this year requires companies to bring foreign profits back to the U.S., with a tax rate of 15.5 percent on cash and cash-equivalent assets (which do not include live chickens, as it turns out) and 8 percent on profits invested in hard assets such as real estate. This one-time mandatory repatriation of foreign profits provides an enormous discount from the 35 percent tax rate companies faced before the passage of the GOP tax cuts in December.

How much cash? U.S. firms were holding roughly $1 trillion in cash offshore at the end of 2017, the Fed said, most of which was invested in fixed-income securities. (Other estimates put the total closer to $3 trillion.) According to balance of payments data, U.S. multinationals repatriated a bit more than $300 billion in the first three months of the year. By comparison, the temporary tax holiday passed in 2004 resulted in the repatriation of $312 billion during all of 2005.

Where did the money go? The Fed report pointed out that the movement of funds is largely a technical matter, noting that “repatriation reflects the transfer of funds to the United States in purely accounting terms: The funds previously held by a foreign affiliate are now held by the U.S. parent.” But what are essentially changes in accounting are having a powerful effect on investors in the form of stock buybacks. “The analysis detailed here suggests that funds repatriated in 2018:Q1 have been associated with a dramatic increase in share buybacks,” the report said.

What about the domestic investments that were supposed to soar as a direct result of the windfall? “[E]vidence of an increase in investment is less clear at this stage, as it is likely too early to detect given that the effects may take time to materialize,” the report said.

A closer look at the biggest firms: The Fed analyzed buyback, dividend and investment data for the 15 non-financial firms with the largest cash holdings overseas, which together account for about 80 percent of the total. For that group, buybacks more than doubled (from $23 billion to $55 billion) between the fourth quarter of 2017 and the first quarter of 2018. Dividends, however, were little changed, and there was no obvious spike in investment, although it’s probably too early to reach any conclusions on the latter point. The results confirm earlier studies of the 2004 tax holiday, the Fed said, which found that repatriated profits tend to be used to fund stock buybacks.

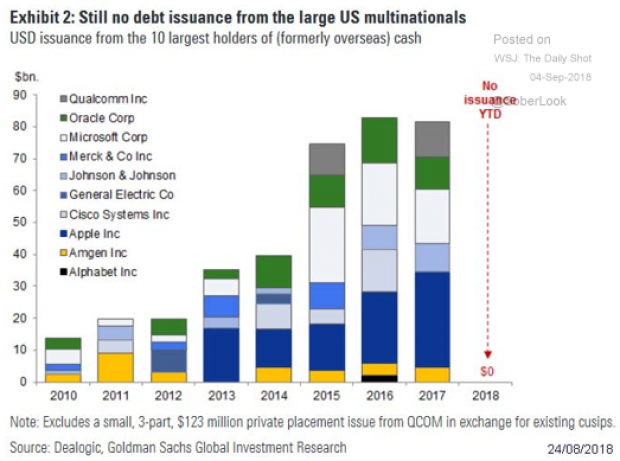

Another notable effect: According to a chart published by The Wall Street Journal earlier this week, based in part on data from Goldman Sachs, the repatriation of profits appears to have had a significant effect on debt issuance by U.S. multinationals with the largest overseas cash holdings. So far this year (the chart is dated August 24), the 10 multinationals with the largest piles of overseas profits have issued no new debt, a significant change from previous years. While this doesn’t tell us anything about how these companies are using their repatriated funds, it does suggest that the tax holiday has sharply reduced their need to borrow money in the financial markets.