|

Long-term unemployment is becoming the defining feature of the Great Recession. As of September, the average time out of work stands at 40.5 weeks. Of the 14 million unemployed, about 45 percent have been jobless for more than six months, and over 70 percent of those have not worked in a year or more. No other business cycle since the 1930s has come close to matching the current experience. After a speech in Cleveland on Sept. 28, Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke called long-term joblessness a “national crisis” in a comment to the Associated Press.

The economic costs of long-term unemployment are much greater than a period of high unemployment that quickly dissipates, such as the 1981-82 recession, when joblessness peaked at 10.8 percent. In the short run, the drag on consumer spending lasts longer. Credit quality remains poor, making banks less willing to lend, especially now amid heavy mortgage defaults. Government budgets stay under pressure much longer. In the long run, productivity suffers, which can cut into the economy’s ability to grow, lowering living standards and making the economy more inflation prone.

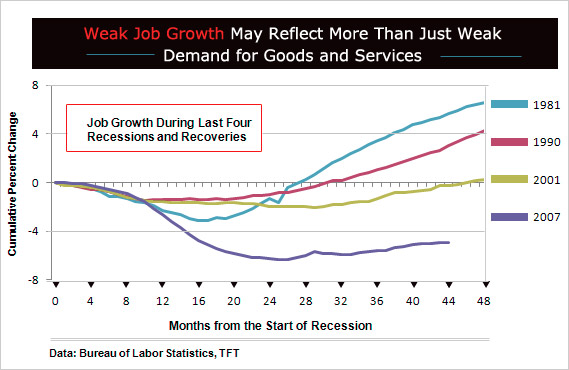

Each monthly job report makes it clear that the current job recession is different from the typical up and down pattern of past business cycles. The Labor Dept. reported Friday that September payrolls rose 103,000, but they have recouped just 24 percent of the jobs lost since the recession began almost four years ago. The unemployment rate last month held at 9.1 percent and except for a dip in February and March, it has remained above 9 percent since the recovery began more than two years ago. Two years after the peak in the 1981-82 recession, the jobless rate had fallen nearly 4 percentage points.

The key question for policymakers is how this labor market is different. Some analysts say today’s persistently high unemployment reflects weak demand for goods and services, and policy stimulus to boost spending will put people back to work. However, many economists are starting to fear that the U.S. may never return to the days of 5 percent or less unemployment. That’s because the long-term jobless are losing their skills and their employment connections, and are drifting further away from the labor force. The most effective policy in that case would be retraining for the unemployed and education geared toward growth industries, especially at a time when ever-greater global competition is reshaping the U.S. industry.

People are less likely to move from unemployment to employment the longer they are out of work. Of people who have been jobless for more than 12 months, only about 1 in 10 have returned to work, while about 90 percent have either remained unemployed or dropped out of the labor force, according to a Labor Dept. study. Since the recession began, the labor force participation rate, defined as the percentage of the population aged 16 and over who are employed or seeking work, has fallen by the most in post-war history to levels not seen since the early 1980s.

Those without a college degree face nearly 10 percent

unemployment, while the rate for college graduates

is 4.2 percent.

Studies show that the extension of unemployment benefits—to 99 weeks in some states—has lengthened the average duration of unemployment by about two to six weeks. However, analysts at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond in a recent research paper note that since the extension, the average duration has increased by 18 weeks, suggesting that much more is at work than the benefit program’s disincentive to look for work. “After a long period of unemployment, affected workers may become effectively unemployable,” they say.

The increasingly disenfranchised workers generally include youth, the less educated, and industries most affected by the recession, especially construction, where unemployment is more than 13 percent. The jobless rate for teenagers, 16 to 19 years old, is nearly 25 percent. For those aged 20 to 24, it’s almost 15 percent. For those 25 and older, education is the dividing line. Those without a college degree face nearly 10 percent unemployment, while the rate for college graduates is 4.2 percent.

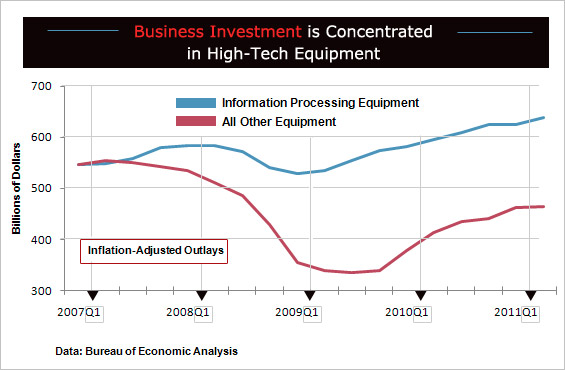

These high jobless rates highlight a key problem. “Long-term unemployment arises because there is a mismatch between the skills demanded by employers and the skills offered by workers,” say economists at Wells Fargo Securities in a recent study. They note that many employers, especially in fast-growth technical fields, go begging for workers, given that construction workers cannot easily transition to jobs in computer technology or software development or healthcare, while youth lacks experience, and the less educated are left behind.

The pattern in business investment, for example, shows strong demand for high-tech goods and services—and the workers that produce them—despite an otherwise lackluster economic recovery. Business outlays for high-tech equipment and software barely missed a step during the recession, and they now stand 10 percent above their pre-recession level. Spending on all other lower-tech equipment remains 14 percent below the pre-recession mark.

Policymakers at the Federal Reserve are divided on how to address long-term unemployment. Some believe that growing skill mismatches have already affected the economy’s long-run growth potential. Some private-sector economists agree. They say that effective “full employment” may now be a jobless rate of 7 percent or more, not the generally accepted 5 percent or so prior to the recession, and that trying to push unemployment below that level would only put upward pressure on inflation. This is one reason why some policymakers oppose the Fed’s recent move toward more monetary stimulus.

Fed Chairman Bernanke argued in an August speech that short-run policies aimed at minimizing the duration of unemployment will help to avoid skill-erosion and loss of attachment to the labor force, thus reducing the long-run effects of long-term unemployment on the economy. President Obama’s jobs proposal includes programs similar to state programs in Georgia and New Hampshire that encourage companies to train workers while they receive jobless benefits, in addition to tax credits for companies that hire long-term unemployed job seekers.

All policymakers agree that long-term unemployment can have long-run consequences for the economy, problem is they still haven’t figured out is what to do about it.