A year after it began, the Ebola epidemic in West Africa continues to be unpredictable, forcing governments and aid groups to improvise strategies as they chase a virus that is unencumbered by borders or bureaucracy.

The people fighting Ebola are coming up with lists of lessons learned — not only for the current battle, which has killed more than 7,500 people and is far from over, but also for future outbreaks of deadly contagions.

Related: The Virus That's More Likely to Kill You Than Ebola

Many of the lessons are surprising and specific — the color of body bags turns out to be important, as does the design of Ebola clinics. The most common-sense lesson is that all Ebola is local; solutions can’t be dictated from Geneva or New York.

The broader and more ominous lesson is that global health organizations aren’t ready for a pandemic. There are countless conferences, reports and carefully wrought strategies for stopping epidemics, but this terrible year has demonstrated how hard it is to get resources — even something as simple as bars of soap and buckets of bleach — to vulnerable people on the front line of an explosive disease outbreak.

Man vs. microbe is certain to be a recurring narrative in the 21st century. It’s a natural consequence of a burgeoning human population. Our vulnerability to new pathogens will not be easily fixed.

LESSON: Rely on the local leadership.

When Peggy Chilcott looks back on the great Ebola outbreak of 2014, she will picture herself in a remote village in West Africa where the inhabitants feared that outsiders had come to poison them.

Related: 11 Ways to Fight Ebola and Other Diseases

Chilcott, 34, a doctor with the charity group Samaritan’s Purse, traveled from Spokane, Wash., to Liberia in November. One day she and two colleagues made a journey by helicopter to a remote village in Gbarpolu County, north of Monrovia. Two people there had tested positive for Ebola.

The villagers were skeptical of the outsiders and their medicines, which included malaria pills. Go away, one man said, “and take your poison with you.” Chilcott tried to reassure them by swallowing pills as they watched. But the mood became increasingly hostile. Alarmed, Chilcott sent an emergency satellite signal for the helicopter to return. It arrived in 21 minutes and swooped everyone away before they had even buckled their seat belts.

That wasn’t the end of the story, however. A regional chief intervened. He vouched for the integrity of the foreign health workers and pleaded for them to return to help people survive the deadly contagion. The village also exiled a local troublemaker.

With the level of trust higher, Chilcott, her colleagues and other aid workers trekked back through the rain forest to the village and this time were greeted with smiles and clapping.

Related: New Rapid Test for Ebola Gets FDA Approval

Countless variations of this story have played out across West Africa. “You can’t just blast into a place and expect people to drop everything and do what you tell them to do,” says David Nabarro, the U.N. special envoy on Ebola. “They have to be utterly convinced your motives are good. They have to be able to share their view with you.”

Archie C. Gbessay, a Liberian who is coordinator of the Active Case Finders and Awareness Team in Monrovia, said recently that if foreign intervention and billions of dollars in contributions were all it took to stop the disease, “we should already be celebrating the eradication of Ebola from my country.”

This same lesson was hammered home by Monique Nagelkerke, who recently wrapped up two months as the head of mission in Sierra Leone for Doctors Without Borders. “It’s the experts that get interviewed, but it’s people from the region themselves that come to work day after day,” Nagelkerke said. “They are the real heroes.”

LESSON: Be sensitive to peoples’ cultures.

Julienne Anoko, an anthropologist working on the Ebola response in Guinea, faced a situation involving a pregnant woman who had died of Ebola with her dead baby inside her. Tribal custom required that the baby be removed from the womb and buried separately. The doctors forbade the baby’s removal, saying such surgery could spread the disease.

Related: Ebola: Obamacare's Ultimate Pre-Existing Condition

Anoko had to find a way to satisfy the family and the medical establishment. She tracked down an 80-year-old ritualist. He put together a culturally acceptable set of rituals that included the sacrifice of a goat and prayers to appease the ancestors.

The people suffering through this epidemic, Anoko said, “have something to say, and it’s important to listen to them first, instead of building solutions elsewhere and saying to the community, ‘We know your problem; this is the solution.’ ”

LESSON: Simple changes can yield significant results.

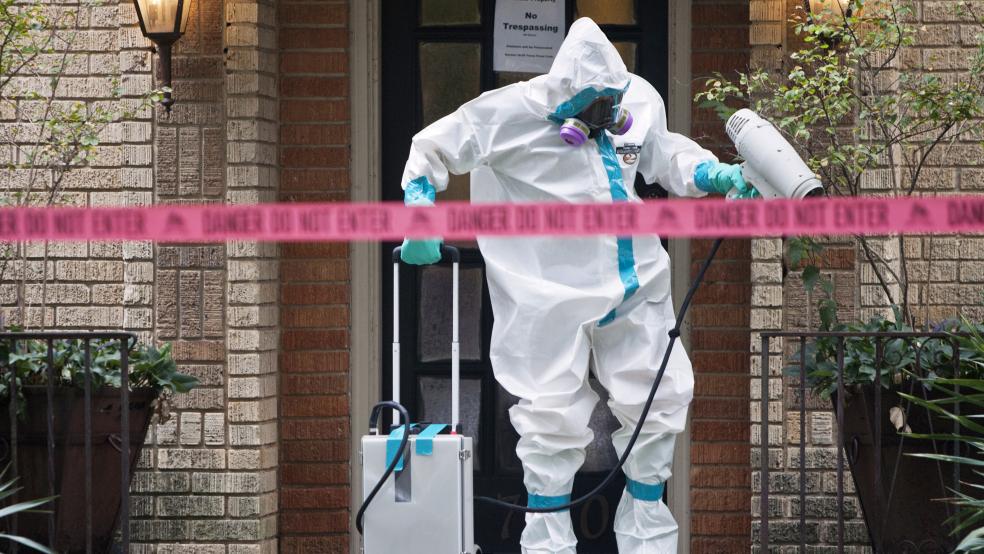

Many lessons were learned on the fly, in crisis mode, and they amounted to slight adjustments in tactics based on feedback from locals. For example, Western aid workers initially used black body bags for burials in Liberia. But white is a traditional color of mourning, especially for Muslims, and Liberians balked. Simple fix: Officials ordered white body bags.

Another simple innovation involved the design of Ebola treatment units (ETUs).

“By the end of July, no one had ever heard of an Ebola treatment unit, and at the same time there was a requirement to move fast, at scale, and mount a response that could intercept this crazy, increasing infection rate,” said Nancy Lindborg, a top official at the U.S. Agency for International Development.

Related: How Other Countries Are Preparing to Stop Ebola

Family members didn’t want to send loved ones to the centers, afraid they might never see them again. They had seen too many people simply vanish. Officials came up with an innovation: transparency. They replaced walls with fences and added windows, which improved air circulation and offered a glimpse inside.

“Make it look less like Guantanamo Bay and make it more of a patient-friendly kind of environment,” Nagelkerke said.

LESSON: Speed and agility matter more than size.

Ebola has repeatedly outfoxed and outraced global responders.

The United States developed a plan in late summer for a massive intervention in Liberia, centered on the construction of up to 17 large Ebola treatment units — but then the infection rate began dropping rapidly.

The result is that Americans are, at great cost, finishing ETUs that have many beds but few patients. These are temporary structures that can’t be used for other purposes and, when the epidemic is over, will probably be burned to the ground.

Related: ISIS and Ebola Concerns Dominate Mega-Spending Bill

Meanwhile, Sierra Leone has surpassed Liberia as the country with the highest infection rate. The global response has been divided up along colonial-era lines: Britain is focused on Sierra Leone and France on Guinea.

The United States is starting to shift some resources to Sierra Leone, deploying additional personnel under the auspices of USAID, sending two Defense Department laboratories and talking to nongovernmental organizations and other global partners about dispatching more of their health-care workers, according to a senior administration official.

“You can get a strategy and it becomes an immovable constraint,” Lindborg said. As the epidemic has evolved, she said, the United States has decided to shift to “a rapid-response strategy” aimed at smothering Ebola wherever it pops up. “You have to be adaptable to the course of the disease.”

LESSON: We’re all connected — and unprepared for the consequences.

In an increasingly interconnected world, affluent countries have to be aware of — and care about — what’s happening in the poorest.

“This is the poster child for why we should pay attention to fragile states,” Lindborg said. “This is a wake-up call. Thank God it was Ebola and not something airborne.”

Related: 9 Ways Robots Could Help Battle Ebola

Ken Isaacs, head of Samaritan’s Purse, the North Carolina-based Christian missionary organization that has been working in West Africa, argues that the global community cannot merely rely on the World Health Organization, which has a decentralized management structure and got caught flat-footed by Ebola. He would like to see a new structure formed, one with political leverage, laboratory research capabilities and a global reach.

Experts have warned for years that all countries need to do more to improve their ability to detect and curb outbreaks. Multiple initiatives on that front have had mixed results.

In February, in the middle of a Washington snowstorm, the White House launched the Global Health Security Agenda. The United States has pledged to help 30 countries bolster their capacity to deal with biological threats of any kind, from natural epidemics to bioterrorism. Vulnerable countries should also take several steps to protect themselves, such as identifying and tracking the most prevalent deadly pathogens and being able to activate an emergency operations center within hours of an outbreak.

In the current epidemic, countries in West Africa were slow to create a functional “incident command” structure, one in which officials were empowered to make decisions quickly.

Related: 'Lie' of the Year and the Forgotten Ebola Truth

Money for the Global Health Security Agenda is materializing: Congress just approved over $5 billion in emergency Ebola funding, more than $800 million of which will go to efforts to stop future epidemics.

LESSON: An ounce of prevention...

The year of Ebola showed that it is a lot cheaper and easier to stop a viral outbreak early, before it metastasizes into a full-blown epidemic. But that common-sense notion collides with another one: Watching out for emerging diseases and other proactive efforts aren’t terribly glamorous.

The epidemic that didn’t happen is like the nuclear power plant that didn’t have a meltdown — desirable, but not headline-grabbing. That can make such efforts a tough sell, politically. Ebola surveillance and research is now getting abundant funding, but Ebola isn’t necessarily the most dangerous pathogen that humanity could face in the near future.

“We’re always chasing what just happened,” said Jonna Mazet, a professor of epidemiology and disease ecology at the University of California at Davis and the director of the Predict project, a disease-surveillance program funded largely by USAID and operating in 20 countries.

Related: Ebola's Long Tail of Devastating Economic Harm

The project Mazet oversees has set up dozens of labs in the developing world. It has tested thousands of animals — bats, rats and monkeys among them — and identified about 800 previously unknown viruses.

“If we don’t start getting ahead of the curve on pandemics, we’re sitting here like victims waiting for the next one,” said Peter Daszak, a well-known disease ecologist who works on the same project.

In an office 17 floors above West 34th Street in Manhattan, analysts working for Daszak pour data into complex mathematical models, trying to decipher the most likely places an epidemic might surface next. The data behind those “heat maps” come from intense detective work around the globe, from Thailand and Tanzania to Bolivia and Bangladesh.

In Vietnam, for example, researchers affiliated with Oxford University head out almost daily to slaughterhouses and animal farms. They visit open-air markets teeming with ducks, porcupines, bamboo rats and other animals to understand what viruses and bacteria the animals harbor and to watch closely for the moment any of them might infect humans.

Related: The High Cost of Having Ebola-Ready Hospitals

This kind of work is more crucial than ever, said Mark Woolhouse, a professor of infectious disease epidemiology at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland. “The early 21st century is about as good as it gets for emerging viruses and pathogens,” he said. “Changes in trade, travel and population — it’s a perfect storm for viral emergence.”

LESSON: Keep fear in check.

When Tom Frieden, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, visited Liberia in August, he went to a crematorium that operated day and night as the bodies of Ebola victims were immolated. Soon afterward, he developed a nosebleed. “To have blood spurting out of your nose in the middle of an Ebola outbreak is a little bit anxiety producing,” he recalled.

Rationally, he knew he didn’t have Ebola. He figured the nosebleed was caused by the dryness from his recent flight. His main concern was that people would think he had Ebola. But even the CDC director wrestled with nagging doubts about his health. “You worry about every symptom, like a sore throat,” he said, “even if you had no chance of being infected.”

One of his deputies, Jordan Tappero, spent five weeks in Liberia in late summer and had a bout of travelers’ diarrhea. “Stuff goes through your head when you’re getting up in the middle of the night,” Tappero said. “I was always able to talk myself off the ledge.”

Related: Why Survivors Could Hold the Key to an Ebola Cure

These anxieties were minor compared with the national hysteria that accompanied the Ebola epidemic when it crossed the Atlantic. More than one school system shut down over a worry that the parent of a student possibly had contact with an Ebola victim. A controversy broke out over whether returning humanitarian volunteers should be quarantined for weeks. Scientists who had been to West Africa were disinvited to a medical conference.

In mid-October, a U.S. Coast Guard helicopter and plane were dispatched to a cruise ship off the coast of Mexico to obtain blood samples from a passenger on vacation. She had, 19 days earlier, been working in a lab at a Dallas hospital and possibly had come in contact with a sealed vial of blood belonging to Thomas Eric Duncan, a Liberian who became the first person to die of the disease in the United States. She had no symptoms.

The plane flew her sample to Austin, where lab technicians confirmed what doctors already knew: She did not have Ebola. The Coast Guard spent $86,256 to retrieve and deliver the blood, an agency spokesman said. This eruption of alarmism came despite repeated assurances from experts that Ebola is not very contagious, as viral diseases go. The only two people who caught Ebola in the United States were nurses caring for Duncan.

But Frieden acknowledges a basic mistake in his communication efforts. In a Sept. 30 news conference after it was confirmed that Duncan had Ebola, Frieden assured the public that the virus wouldn’t spread here. “I have no doubt that we will stop it in its tracks in the U.S.,” he said.

Then the two nurses got sick.

Frieden’s words, on their face, were correct: Ebola did not “go viral” in the United States. But his confident language implied an element of certainty that is hard to back up during an evolving public-health emergency. “Clearly I did not convey adequately the degree it was going to be hard” to stop the virus, Frieden recently told The Washington Post, “and that we would be adjusting and learning.”

Lenny Bernstein contributed to this report, which originally appeared in The Washington Post.

Read more in The Washington Post:

A missing jet and the truth about Indonesia's troubled aviation history

I stopped eating food that comes in a package. I've never felt better.

Kansas is the best state in America