Tiny Bubbles, Big Business: How Seltzer Became the Hot New Drink

Struggling to decide between healthy but boring water and sweet, sugary soda, Americans are increasingly turning to fizzy water to quench their thirst.

Although soda remains the leader in the soft drink category, soda consumption has fallen for the 10th year in a row, to the lowest level since 1986, according to The Wall Street Journal. Americans have been dropping sugary soda for years due to health concerns, but lately even diet soda has been losing popularity over worries about artificial sweeteners.

Sales of fizzy water — the category includes such well-known brands as Perrier and San Pellegrino — have grown to about $1.5 billion a year, more than doubling since 2010, according to data from industry research firm Euromonitor quoted in The Washington Post.

Related: How Coke Beat Pepsi in the New Cola Ad War

One of the top new brands is National Beverage’s LaCroix Sparkling Water, whose dozen flavors of bubbly H20 seem to be aimed at millennials in particular. The brand’s bright, colorful cans convey an alternative vibe, and the drink’s Instagram is loaded with attractive young people hoisting a can at pools, beaches and other relaxing places.

National Beverage credited sparkling water as the main factor that grew the company’s stock 75 percent over the last five years. Sales of the LaCroix brand alone have grown to $175 million, almost tripling since 2009.

Another rapidly growing brand, Sparkling Ice, owned by Talking Rain Beverage Company, saw sales boom to more than $384 million in 2014 from $2.7 million in 2009.

Gary Hemphill, managing director and COO of research at Beverage Marketing, sees the sales of seltzer and sparkling water only increasing as consumer demand for healthier refreshments grows.

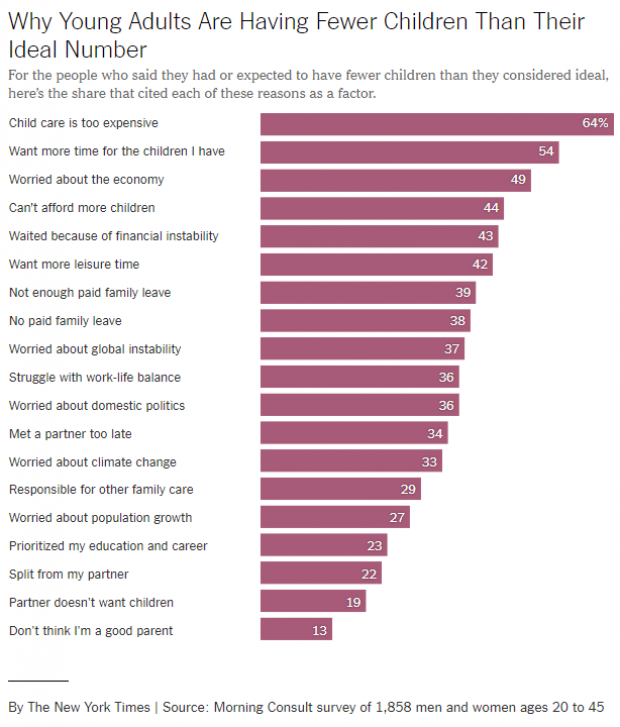

Chart of the Day: Why US Fertility Rates Are Falling

U.S. fertility rates have fallen to record lows for two straight years. “Because the fertility rate subtly shapes many major issues of the day — including immigration, education, housing, the labor supply, the social safety net and support for working families — there’s a lot of concern about why today’s young adults aren’t having as many children,” Claire Cain Miller explains at The New York Times’ Upshot. “So we asked them.”

Here are some results of the Times’ survey, conducted with Morning Consult. Read the full Times story for more details.

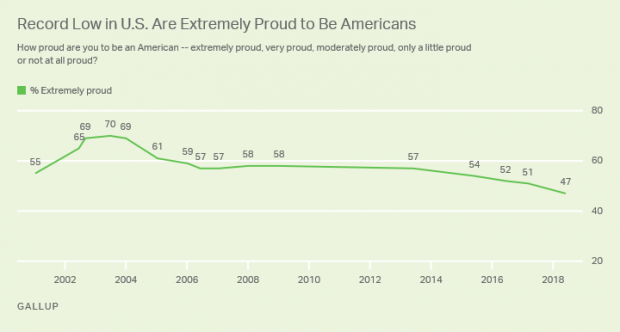

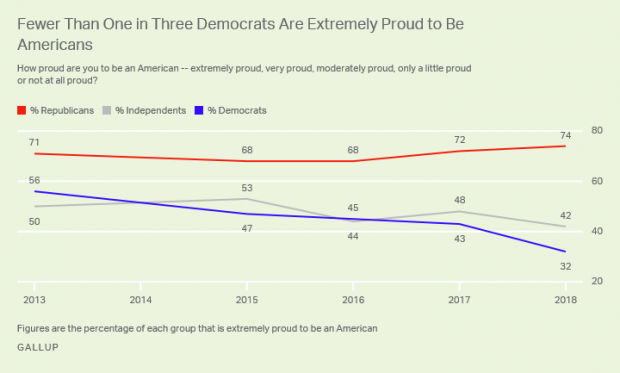

A Record Low 47% of US Adults Say They're 'Extremely Proud' to Be American

Gallup says that, for the first time in the 18 years it’s been asking U.S. adults how proud they are to be Americans, fewer than half say they are "extremely proud." Just 47 percent now say they’re extremely proud, down from 70 percent in 2003.

Another 25 percent say they’re “very proud” — but the combined 72 percent who say they’re extremely or very proud is also the lowest Gallup has recorded. Pride levels among liberals and Democrats have plunged since 2017. Overall, 74 percent of Republicans and just 32 percent of Democrats call themselves “extremely proud” to be American.

Pfizer Has Raised Prices on 100 of Its Products

Weeks after President Trump said that drugmakers were about to implement “voluntary massive drops in prices” — reductions that have yet to materialize — Pfizer has raised prices on 100 of its products, The Financial Times’s David Crow reports:

“The increases were effective as of July 1 and in most cases were more than 9 per cent — well above the rate of inflation in the US, which is running at about 2 per cent. … Pfizer, the largest standalone drugmaker in the US, did decrease the prices of five products by between 16 per cent and 44 per cent, according to the figures.”

Crow notes that Pfizer also raised prices on many of its medicines in January, meaning that some prices have been hiked by nearly 20 percent this year. The drugmaker said that it was only changing prices on 10 percent of its medicines and that list prices did not reflect what most patients or insurers actually paid. The net price increase after rebates and discounts was expected to be in the “low single digits,” the company told the FT.

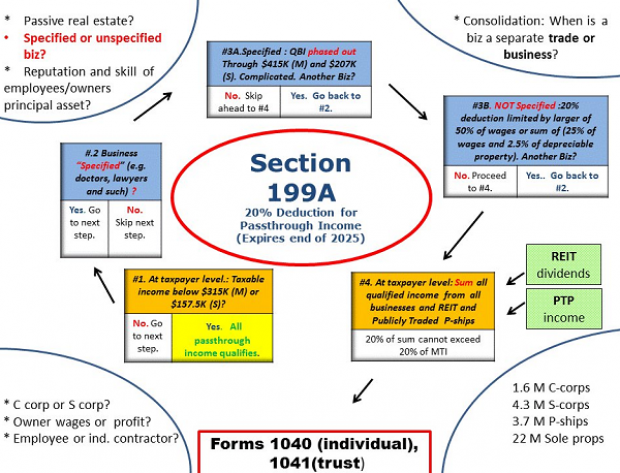

Chart of the Day: Pass-Through Tax Deductions Made Easy

The Republican tax overhaul was supposed to simplify the tax code, but most experts say it fell well short of the goal. Martin Sullivan, chief economist at Tax Analysts, tweeted out a chart of the analysis required to determine whether income qualifies for the passthrough tax deduction of 20 percent, and as you’ll see, it’s anything but simple.

A Conservative Bashes GOP Dysfunction on Spending Cuts

Brian Riedl, a senior fellow at the conservative Manhattan Institute, offers a blistering critique of congressional Republican’s problems cutting spending:

Since the Republicans took the House in 2011, nearly every annual budget blueprint has promised to balance the budget within a decade with anywhere from $5 trillion to $8 trillion in spending cuts. And yet, you may have noticed, the budget has not moved towards balance. This is because the budget merely sets a broad fiscal goal. To actually cut spending, Congress must follow up with specific legislation to reform Medicare, Medicaid, and all the other targeted programs. In reality, most lawmakers who pass these budgets have no intention whatsoever of cutting this spending. As soon as the budget is passed, the targets are forgotten. The spending-cut legislation is never even drafted, much less voted on.

The annual budget exercise is thus a cynical exercise in symbolism. Congress calculates how much spending must be cut over ten years to balance the budget. Then they pass legislation setting a goal of cutting that amount. Then they move on to other business. It’s like a baseball team announcing that they voted to win the next World Series, and then not showing up to play the season.

Read the full piece at National Review.